If You Can Hold This Core Position for 90 Seconds After 50, You’re Stronger Than Most

It’s tough to find a fitness test that can reveal your true strength in under two minutes, but this 90-second plank is one of them. While this plank test may look simple, it feels anything but. And according to coaches who train older adults every day, hitting that full minute-and-a-half plank with clean form after 50 is an objective marker of exceptional stability, control, and functional strength for your age.

After 50, core strength matters more than most people realize. Research shows that core endurance (especially anti-extension and anti-tilt strength) is crucial for maintaining balance, preventing lower back pain, and supporting independence later in life. A solid plank reflects strength not only in the abs but also in the hips, obliques (side abs), and lower back that help you move safely and confidently after 50.

“A 90-second plank is a legitimate strength benchmark at any age,” says Ed Gemdjian, General Manager of The Gym Venice. “It challenges your core, shoulders, hips, and even your breathing control. Holding it for the full time demonstrates real stability and muscular endurance.”

The good news is that older adults can work toward that 90-second plank goal by incorporating smart training, modifying their plank position (if needed), and staying consistent. “Most people over 50 are fully capable of performing a standard plank on elbows and toes, unless they have a specific injury or medical limitation,” says Gemdjian. “Regressions are simply options, not assumptions about ability.”

Below is the complete test, followed by a four-exercise training plan designed by Gemdjian to build the total-body strength needed to reach the 90-second mark safely and consistently. Read on to learn more.

(When you’re finished, don’t miss these 5 Exercises Every Man Over 55 Should Do Daily to Maintain Strength.)

How to Perform the 90-Second Plank Test

Start in a traditional forearm plank position. This means:

- Elbows under shoulders

- Forearms on the floor

- Legs straight with toes on the ground

- Body in a straight line from head to toe

- Set a timer and hold as long as you can for up to 90 seconds.

What to watch for:

- Hips dropping

- Lower back arching

- Head jutting forward

- Holding your breath

If you lose proper form, stop immediately. Quality form matters far more than time. And if you experience any pain (especially in your lower back), that’s your cue to end the test.

What your time means:

- 30 seconds: Solid starting point

- 45 to 60 seconds: Above average

- 60 to 90 seconds: Strong and well-conditioned

- 90 seconds with proper form: Elite

Regressions (if needed):

If a traditional plank is too challenging at first, try these variations instead:

- Plank with your hands on a bench or countertop

- Wider foot stance

- Shorter holds performed multiple times

Progressions (once 90 seconds feels comfortable):

Consider trying these more challenging plank variations after you’ve mastered the 90-second hold:

- Plank shoulder taps

- One-leg plank

- Slow reach outs

- The 4-Exercise Training Plan to Reach a 90-Second Plank

4 Exercise Training Plan to Build A Stronger Core For Longer Plank Holds

For each of the following core exercises, Gemdjian recommends:

- Perform three sets each

- Hold for 20 to 40 seconds each (or 8 to 10 reps for dynamic moves)

- Rest for 45 to 60 seconds between sets

Plank

This is your main training move and the most direct way to increase your plank time. Practice shorter holds with perfect form rather than grinding through sloppy long ones.

How to do it:

- Set up exactly as you would for the test.

- Hold your body in a straight line.

- Maintain steady breathing.

Why it works:

This move trains anti-extension strength, which is essential for protecting your lower back while lifting, standing, or carrying.

Progressions:

- Lift one foot slightly

- Add shoulder taps

Dead Bug

The Dead Bug is a killer core-stability exercise that teaches you to maintain a braced spine while moving your arms and legs, which is exactly the skill required during long isometric holds like the plank.

How to do it:

- Lie on your back with your knees over your hips and your arms straight up.

- Lower your opposite arm and leg toward the floor.

- Return to the starting position and switch sides.

Why it works:

This core exercise teaches you coordinated limb movement helps improve posture and mobility without impacting spinal position.

Progressions:

- Extend your arms and legs lower and slower

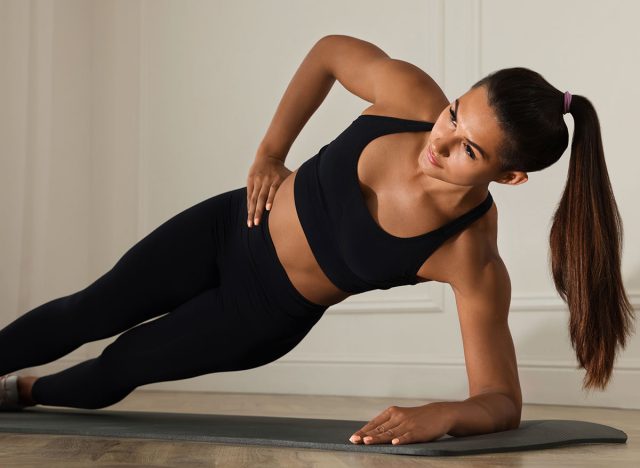

Side Plank

A long plank requires strong obliques (side abs) and hip stabilizers, which are exactly what this movement targets.

How to do it:

- Lie on your side with your forearm under your shoulder.

- Lift hips to form a straight line.

- Hold for the prescribed time.

Why it works:

- Builds lateral core strength that’s essential for balance and hip stability.

Progressions:

- Lift your top leg only

- Hold longer if possible

Suitcase Carry

The Suitcase Carry is one of the best core exercises for mimicking daily movement patterns. That’s because holding weight on one side forces your core to resist tipping, which is a different but critical component of core endurance.

How to do it:

- Hold a dumbbell, grocery bag, or backpack in one hand.

- Walk slowly for 20 to 30 seconds.

- Switch sides.

Why it works:

The Suitcase Carry helps train anti-tilt strength to support gait stability, better posture, and mobility.

Progressions:

- Increase the weight safely or walk longer