Here’s How Cutting Added Sugar Changed My Outlook on My Diet

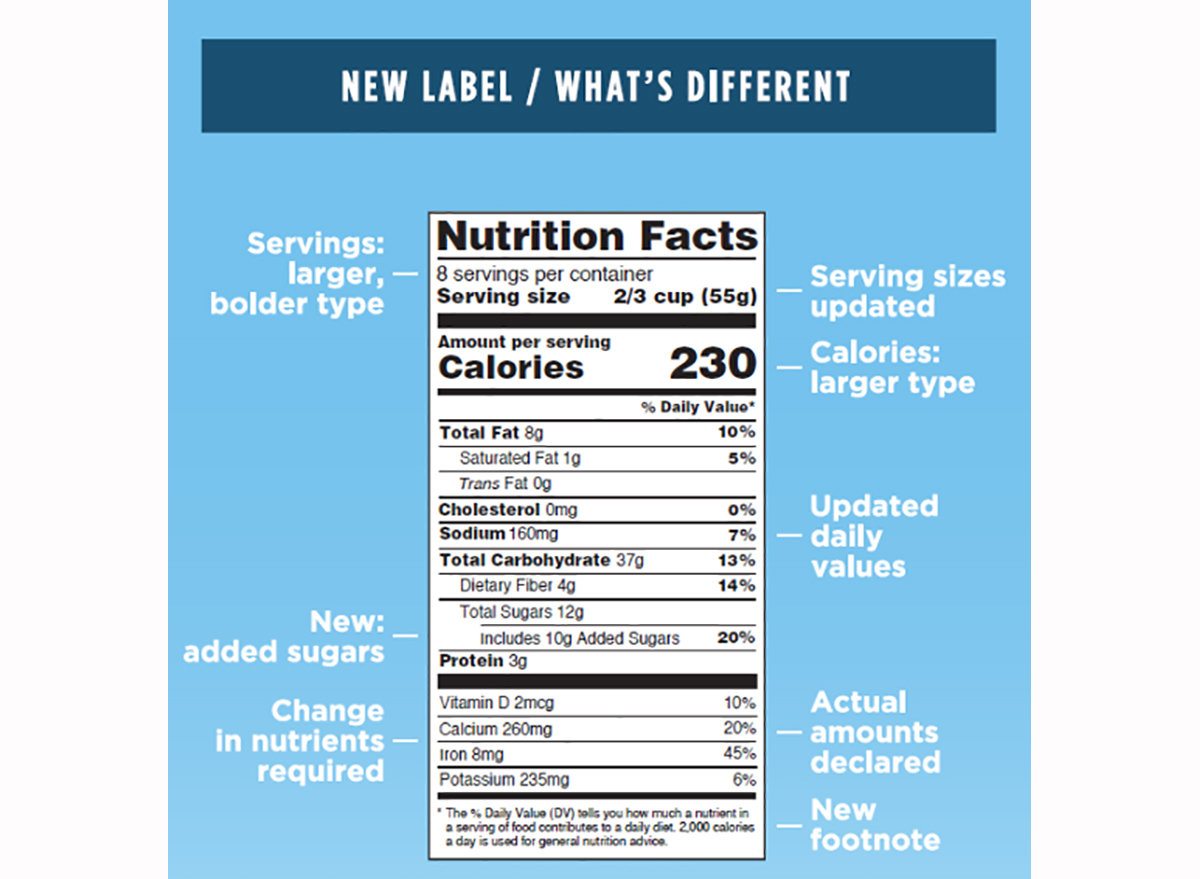

Added sugar lurks in many packaged and processed foods, and you may not even know it. Not all nutrition labels have been updated to demonstrate just how much of the sugar in the food item is added and which are naturally occurring, if any at all. This will all change by 2020 though—with the help of the 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, the Food and Drug Administration called for a nutrition label makeover so that consumers can begin making better-informed decisions about what they’re putting into their bodies. Large food manufacturers have until January 1, 2020, to make the switch, and smaller ones have until 2021. So what does this mean for those trying to figure out how to cut added sugar?

Instead of “Sugars”, the new label will clearly differentiate which sugars are added and which ones are naturally occurring in the food items by breaking them out into two categories, “Total Sugars” followed by the sub-category “Includes X g Added Sugars.”

Enlightened, in part, by this upcoming change in the nutrition label, I decided to go ahead and cut added sugars out of my diet for five days. (Plus, our founder did it for two weeks, and it really made a shocking difference!) I also wanted to practice mindfulness while grocery shopping (taking the time to read the label in full) and to see if I felt like I was addicted to added sugar. I had two friends do this challenge with me, too, and to our collective surprise, we discovered that several food products we regularly consume have sugar added to them.

So in order to properly uncover how to cut added sugar from our diet, we had to first identify which food products to avoid because, again, not all nutrition labels are updated. Instead, we relied on the list of ingredients to tell us if added sugar was sweetening our favorite packaged foods.

RELATED: The easy guide to cutting back on sugar is finally here.

What’s the difference between added sugar and naturally occurring sugar?

Added sugar is described as sugars and syrups that are added to foods and beverages during process or preparation to help make the product more palatable and so that it can stay on the supermarket shelves longer. According to the guidelines, added sugars also “contribute to functional attributes such as viscosity, texture, body, color, and browning capability” in foods as well. Naturally occurring sugars include fructose (found in fruits) and lactose, which is found in cow’s milk.

Added sugar can take on many different names, including molasses, high-fructose corn syrup, glucose, brown sugar, sucrose, and organic raw sugar. Don’t let the organic plug fool you either—it’s still added to foods to make them sweeter. There has been an ongoing debate about whether or not maple syrup and honey should be classified as added sugar. Aside from the rest of the added sugars, pure honey and 100 percent maple syrup are inherently naturally occurring sugars, meaning no sugar is added to make them sweet. Where the discussion becomes complicated though is the notion that you wouldn’t eat maple syrup or honey on their own, you would add it into a smoothie or on top of pancakes. It’s quite literally a sticky situation.

The FDA recently came to a consensus in the final guidance of The Declaration of Added Sugars on Honey, Maple Syrup, and Certain Cranberry Products that a “†” symbol should immediately follow the percent daily value of added sugars. This indicates that the sugar content is coming from what the FDA calls a single-ingredient sugar source, and no additional sugars were added to this product.

Full disclosure: I stirred less than one tablespoon of 100 percent pure maple syrup into my steel cut oatmeal each morning while on the cleanse because of its rich antioxidant content and low glycemic index, which means it doesn’t cause your blood sugar levels to rapidly increase (and then crash) as quickly as honey or sucrose (table sugar) would. I also genuinely love the taste of maple and prefer to consume a single-ingredient sugar derived from nature rather than a packet of oats sprinkled with a mixture of cinnamon sugar crystals.

Why is added sugar a health concern?

Adult and child obesity rates are on the climb, as is the prevalence of type 2 diabetes among both groups. Unhealthy eating habits are largely to blame for these increasing rates, and one ingredient that’s perpetuating these health conditions are added sugars, which increase visceral fat (belly fat). Excess visceral fat, specifically fat that resides between the abdominal organs, is associated with health complications, including cardiovascular disease and diabetes.

The FDA recommends that one devotes no more than 10 percent of their daily calories to added sugar, which is 50 grams of added sugar if you consume 2,000 calories a day. However, the American Heart Association suggests an even lower daily consumption of added sugar at 25 grams for women and 36 grams for men. We decided to try cutting added sugar out completely from our diet for 5 days.

What I learned after cutting added sugar out of my diet for 5 days.

I follow a gluten-free diet (a majority of the time) for health reasons—I learned in 2018 that I have developed a sensitivity to the wheat protein—and I was shocked that something as bland as a plain, gluten-free tortilla contained 3 grams of added sugar. I also realized the sunflower butter I regularly purchase contains added sugar. I often frequent health food stores such as Whole Foods, but I am not always cognizant of the sugar content in some of the foods I buy, namely frozen gluten-free pizzas, granola, and even blueberry preserves.

I don’t drink soda, sweet tea, or chocolate milk, and I eat a lot of fruits and vegetables, so I assumed that my added sugar intake was fairly low. My friends also thought similarly. That is, until we did this challenge and took a close look at the labels on the foods in our refrigerators, freezers, and pantries.

One of my friends discovered the vanilla almond milk she was using to make her homemade cup of oatmeal contained 10 grams of sugar per 8 ounces. In fact, cane sugar is listed before almonds on the ingredients list, meaning there is a greater concentration of sugar in the almond milk than there are almonds. She also stopped using Italian dressing on her salad and, instead, plopped a dollop of either hummus or Trader Joe’s avocado tzatziki on top of the bed of greens.

My other friend resisted willingly indulging in treats such as cupcakes and bagels anytime they were offered in her office. She also skipped the bun for homemade turkey burgers, because added sugar was in the buns she had formerly bought.

This challenge helped me reconnect with a concept called intuitive eating. I closely monitored what I packed for snacks and meals and, as a result, I didn’t allow myself to mindlessly snack, but rather listened to my body for hunger cues. I also swapped out snacks such as gluten-free granola bites and pretzels for slices of mango, cubes of cantaloupe, or a handful of strawberries.

None of us weighed ourselves before or after the challenge, because weight loss wasn’t the incentive of this challenge. We all agreed that we felt better after cutting added sugar, likely because we introduced more whole foods such as fruits and vegetables into our diet and removed almost all processed foods. The best part? It wasn’t challenging. Now, we are more aware of what foods contain added sugar and feel driven to continue to limit our overall consumption of it by making simple swaps.